Utah Wanted All the Tourists. Then It Got Them.

As red-rock meccas like Moab, Zion, and Arches become overrun with visitors, our writer wonders if Utah's celebrated Mighty Five ad campaign worked too well—and who gets to decide when a destination is "at capacity."

Heading out the door? Read this article on the Outside app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

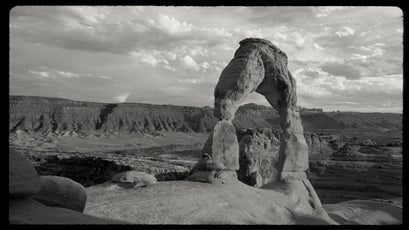

Utah had a problem. Shown a photo of Delicate Arch, people guessed it was in Arizona. Asked to describe states in two adjectives, they called Colorado green and mountainous but Utah brown and Mormon. It was 2012. Up in the governor’s Office of Tourism, hands were wrung. Anyone who had poked around canyon country’s mind-melting spires and gurgling green springs knew it was the most spectacular place on the continent—maybe the world—so why did other states get the good rep?

The office hired a Salt Lake City ad firm called Struck. The creatives came up with a rebrand labeled the Mighty Five, a multimedia campaign to extol the state’s national parks: Zion, Bryce Canyon, Capitol Reef, Canyonlands, and Arches. By 2013, a 20-story mashup of red-rock icons towered as a billboard over Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles. A San Francisco subway station morphed into a molten ocher slot. Delicate Arch bopped around London on the sides of taxicabs. The pinnacle was a 30-second commercial that was—let’s face it—a masterpiece.

An attractive, young, and somewhat cool family of four—Dad sports shaggy hair to the chin, stubble, and wraparound sunglasses—takes a road trip for the ages. They splash through the trippy slo-mo waterdrops of a slot canyon seep, spin beneath psychedelic pillars the voice-over calls “giant orange drip castles,” behold a rapturous explosion of Milky Way stars framed by rock walls, punch their J-rig through a gargantuan wave in Cataract Canyon. Then finally—and this is the shot I’m sort of embarrassed to admit still fills my eyes with tears—the little girl, who’s about ten years old, scrambles along a slickrock bench with a headlamp in the dark until she catches a heart-stopping sunrise glimpse of… well, you’ll just have to watch it yourself.

“I was like, Holy crap,” says Lance Syrett, chairman of the state’s Board of Tourism Development, remembering his first viewing. “You get that feeling—like hair standing on end—this is lightning in a bottle!”

I lived and guided in these canyons for over a decade, and the ad plucked all my heartstrings. It evoked the hardscrabble seclusion of Ed Abbey and the mad descent of Everett Ruess and the soul serenity of Terry Tempest Williams, yet it promised that you don’t have to be a hermit or daredevil: the Cool Family Robinson managed to follow their bliss, apparently, in a Subaru.

“It was laughably simple,” says Alexandra Fuller, the former creative director of Struck. “Taking natural features that have been there forever and parks that have been there for decades and putting it together with a new brand.”

The campaign introduced to the mainstream a type of adventure that for decades had only a cult following. Unlike traditional park fare—peaks, woods, wild animals—canyons are an acquired taste, less achievement and more mystery, an immersion into the stone innards of creation that can be at once sensual, hallucinatory, and religious.

The Mighty Five campaign was a smash. The number of visitors to the five parks jumped 12 percent in 2014, 14 percent in 2015, and 20 percent in 2016, leaping from 6.3 million to over 10 million in just three years. The state coffers filled with sales taxes paid on hotels and rental cars and restaurants. The Struck agency brags that the state got a return on its investment of 338 to 1. The clink of crystal flutes bubbling with Mountain Dew echoed across the land.

And then, on Memorial Day weekend of 2015, nearly 3,000 cars descended on Arches National Park for their dose of Whoa. Inside, all 875 parking places were taken, with scores more vehicles scattered catch-as-catch-can. The line to the entrance booth spilled back half a mile, blocking Highway 191. The state highway patrol took the unprecedented step of closing it, effectively shutting down the park. Hundreds of rebuffed visitors drove 30 miles to Canyonlands, where they waited an hour in a two-mile line of cars.

Since then, Arches has been swamped often enough to shut its gate at least nine times, including the most recent Labor Day weekend. Meanwhile, in Zion, hikers wait 90 minutes to board a shuttle and an additional two to four hours to climb the switchbacks of Angels Landing. There, visitors sometimes find outhouses shuttered with a sign that, although specific to excrement, might well express the condition of the Utah parks as a whole:

“Due to extreme use, these toilets have reached capacity.”

A.B. Guthrie Jr.’s novel The Big Sky tells of a young man who heads west from Kentucky, hoping to track down his mountain-man uncle. But when he reaches Montana, Uncle Zeb has soured.

“The whole shitaree! Gone, by God,” laments Zeb. “This was man’s country onc’t. Every water full of beaver and a galore of buffler any ways a man looked, and no crampin’ and crowdin,’ Christ sake!”

“It ain’t spoilt, Zeb,” someone dissents. “Depends on who’s lookin’.”

“Greenhorns on every boat, hornin’ in and sp’illin’ the fun. Christ sake!” Zeb says. “Why’n’t they stay to home? Why’n’t they leave it to us as found it? God she was purty onc’t. Purty and new.”

The year was 1830.

I’ve heard Uncle Zeb in my own rants over the past 25 years, lamenting the ruination of my personal West: the canyons around Moab circa 1990. They remain in my memory purty and new: a hardscrabble outpost where just about any dirtbag could roll into town, get a job washing dishes or rowing rafts, park a rig on dirt roads galore and live rent-free, no crampin’ and no crowdin’.

It’s no longer the same place. Moab is the gateway to Arches—the second smallest of the Mighty Five, where famous landmarks like Delicate Arch, Fiery Furnace, and the Windows are reached by a single dead-end road. More than any other town, it has borne the brunt of the tourism spike. While the county population has grown incrementally in 30 years, from roughly 6,500 to 9,500, and where there was once a dozen or so low-rise, low-rent, mom-and-pop inns with names like the Prospector Lodge and the Apache Motel (“Stay where John Wayne stayed!”), there’s been a flabbergasting growth in lodging: there are now 36 hotels and 2,600 rooms, plus 600 overnight rentals and 1,987 campsites. There’s no way to track how many people occupy each, but on a fully booked holiday, with a moderate estimate of three tourists per unit, that’s at least 15,000 people, vastly outnumbering the locals. Traffic jams extend from tip to tail, and the two-mile drag down Main Street is a 30-minute morass.

Rents have skyrocketed, because hundreds of homes are now used as overnight lodging. Camping now costs twenty bucks a night, and workers pay upward of $500 a month to share rooms in “bunkhouses” converted by employers.

I still own my little piece of the past, a single-wide on an acre of thistle on a dirt lane by a creek, and each time I return, my heart cracks a little at yet another plywood box stuccoed into a ComfortSleepDaysExpressSuites, at the jacked-up dune buggies revving down Main Street like the Shriners of the Apocalypse, and at the once secret swimming hole overflowing with greenhorns.

And so it was with a blossom of dread that I planned a Labor Day excursion to investigate this story. I live in Albuquerque, New Mexico, now, and my trailer was rented, so I approached Moab as a regular tourist. Five weeks in advance, I snagged the last available ticket online for a guided hike through Fiery Furnace in Arches. The receipt said, “Expect possible delays at park entrance booth and on park roads.” In a town where I used to pay a hundred bucks a month in rent, even the middling motels now cost two hundred a night. My visit coincided with the opening of a new Hilton called the Hoodoo, which that weekend was charging a cool $330. Per night.

Hoo gonna doo that?

On Friday evening, I checked into a decades-old motor lodge instead, where my room was neither a cave nor a basement but resembled both. The lot was full. The place used to be a Ramada Inn, generally vacant enough that river guides and cocktail waitresses could easily sneak into the swimming pool after last call for moonlight skinny-dipping. Now there was a tall fence and you needed a key.

My curiosity beckoned me over a footbridge on a creek and down the hot streets to the Hoodoo, built over an old trailer park where I once responded to a roommate-wanted ad and was greeted by an old-timer with a plastic tube snaking from his nose to an oxygen canister that he toted on a small trolley. I assumed, rightly or wrongly, that he’d been a uranium miner and his days were numbered. I was moved by his immediate adoption of “we” statements. “Here’s our radar oven for popping corn,” he said, pointing at the microwave. “And here’s the couch where we’ll watch the VHS.”

The clink of crystal flutes bubbling with Mountain Dew echoed across the land.

Nostalgia comes easy. We don’t just yearn for a place that’s gone, we long for our youth, when we had the freedom and wherewithal to bask in it. When I first moved here, the local alternative paper, Canyon Country Zephyr, proudly boasted that it was “Desperately Clinging to the Past Since 1989.” Searching its archives last month, I found this: “More people are pouring into town than ever before. The record-breaking visitation numbers at Arches National Park in 1991 now look puny compared to this spring so far. There were groups camping in parking lots, lining up at City Market, pitching their tents in back and front yards, occasionally without the permission of the homeowners.”

That was 1992. Those record-breaking visits to Arches back then totaled nearly 800,000 a year, half of what came last year.

We are stuck between two metaphors. Are we the boy who cried wolf, always convinced the whole shitaree is spoil’t, or the frog in hot water, who claims things are just slightly worse, but still OK, until it’s too late and we’re cooked?

I ended up getting free rent in a garage that season, so I never watched Titanic with the old miner. I remembered him as I approached the shimmering glass and modernist cubes of flagstone at the Hoodoo. Audis and 4Runners glimmered in the lot. A variation of a Joni Mitchell melody sang in my head: They paved a trailer park, and put in a paradise.

Peering through the glass into the foyer, I saw only one person, a uniformed maid, bent low in the mood lighting, polishing with a white towel a pair of steel pigs.

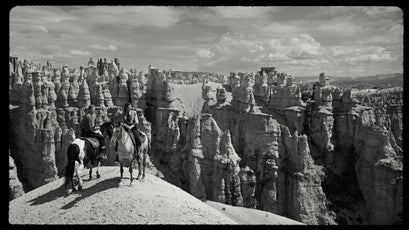

Maybe we can think of the Utah Office of Tourism as Dr. Frankenstein, and its Mighty Five campaign as the glorious creature run amok. (Disclosure: Outside has run ads from the campaign, as well as other ads by the Office of Tourism.) “It has been said by others that it’s almost like some type of nuclear weapon,” says Lance Syrett, chairman of the tourism-development board that oversees the office. He’s the fourth-generation owner of a cluster of hotels perched on the rim of Bryce Canyon, and he speaks with a likeable country frankness. “They say it works too well. We need to lock it away and not use it anymore.”

I watched a video from this past spring, when Vicki Varela, director of the office, addressed a travel-industry conference in Cedar City, Utah. She wore a camel-colored blazer and an earth-tone scarf, exuding a can-do casualness that made her seem as approachable as a PTA mom and as capable as a Fortune 500 boss. She has proven a great bridge builder; when the federal-government shutdown of 2018 caused many parks to close for 35 days, Varela’s office brokered a deal between two hostile factions—the State of Utah and the National Park Service—to keep the Mighty Five open for Christmas. From the podium, she boasted that tourists spent $9.75 billion in Utah in 2018, which translated to $1.28 billion in tax revenue, or between $1,200 and $1,300 in “tax relief” for each household in the state. Tourism accounts for 136,000 jobs, putting it in Utah’s top-ten business sectors.

Of course neither Varela’s office nor the Mighty Five campaign can take full credit for these booming figures or for the onslaught of tourists. Other factors helped. In 2016, the Park Service celebrated its 100th birthday, launching its own ad campaign; between 2013 and 2016, park visits jumped 21 percent nationwide. The past five years have seen a recovery from the Great Recession, low gas prices, and a continued reluctance by Americans to travel overseas. The populations of the nearest big cities—Denver, Salt Lake, and Las Vegas—are booming. And social media creates its own viral marketing. Southern Utah is a victim—or beneficiary—of the global phenomenon of overtourism that has wreaked havoc from Phuket to Venice to Tulum, caused by factors far beyond the purview of state officials: a rise in disposable income, the advent of rock-bottom discount airlines, and innovations like Airbnb and TripAdvisor that have made travel easier and cheaper. Nonetheless, a study by Utah State University economists attributed half a million yearly visitors directly to the Mighty Five ads. Those additional visitors represent a modest, but not insignificant, 5 percent of the ten million annual visitors to the five parks.

When word trickled back in that the ads had worked too well, the Office of Tourism responded. In 2016, it tweaked the campaign, calling it the Road to Mighty and highlighting lesser-known state parks and Grand Staircase–Escalante National Monument, aiming to disperse crowds and spread revenue to other towns. The strategy appeared to work. Visits to the Mighty Five flattened, growing only 4 percent in 2017 and a little more than 1 percent in 2018, while the state parks saw double-digit jumps. (Visits to Grand Staircase grew over the years, but its jump and dips didn’t correspond neatly to the ads.)

Just as Road to Mighty hit the airwaves, President Obama, in January 2017, designated the Bears Ears National Monument, with the support of five Indian tribes. Later, Utah governor Gary Herbert and the state legislature asked President Trump to cancel the monument. Trump slashed Bears Ears by 85 percent and Grand Staircase by half in December 2017.

Still, in 2018, Governor Herbert’s Office of Tourism massaged the campaign again, calling it Between the Mighty and adding Bears Ears to its destinations. At the 2019 conference, Varela said this new iteration of the Mighty Five ads would increase visitor spending, but not the total number of visitors, by targeting a subset that’s more likely to hire a guide than go it alone, glamp instead of camp, and dine on grass-fed leg of lamb drizzled with a balsamic reduction instead of roast weenies on the campfire. What’s more, some resources would be diverted away from advertising into what she called “destination management” and “destination development”—for example, increased signage and trails in the state parks, which she says will reduce visitor impact. Varela also cooed about a new strategy for “addressable TV,” which could target specific customers based on data collected by their cable companies. While one person watching CNN might see a commercial for Oreos, another might see Bears Ears.

Many questioned if crowding could be addressed by sending tourists elsewhere. “National parks are designed to handle these big crowds,” says Kevin Walker, chairman of the Democratic party in Grand County (which includes Moab) and a member of the planning commission. “They put so many people in them that they basically broke them. Now they’re saying, ‘Let’s send them to these places that can’t handle it.’ It’s insane.” As one salty Moabite summed up the new campaign: “They ruined the parks, and now they want to ruin the places in between.”

In Garfield County, which is home to Bryce Canyon National Park and much of Grand Staircase, many locals have resisted their placement on the Road to Mighty. Blake Spalding is co-owner of Hell’s Backbone Grill and Farm in Boulder, population 240. One of the largest employers in the county, and the state’s only restaurant honored as a semifinalist for the James Beard Award, the place is a perfect fit for well-heeled tourists. But when Spalding was approached by the Office of Tourism to appear in its ad campaign, she declined.

“I’m not your good poster girl anymore,” she told me. “Furthermore, I’m furious with the governor. He’s being disingenuous, putting all this money into promoting tourism on the one hand and then actively supporting the diminished funding and protection of the monument.”

When I asked Varela why her office still advertised Lower Calf Creek Falls in Grand Staircase after the cuts to the monument and reports of overcrowding on this trail, she said, “We don’t have written guiding principles about how that was done. We chose what we thought were iconic locations. We have considered if it was problematic to run that ad. We did some due diligence. But that area still has capacity.”

Still, it’s hard not to think the monuments have gotten a double punch: just as visitation jumps, the capacity to handle the visitors with rangers, law enforcement, and toilets has been cut. With jargon like “infrastructure” and “resource management,” the layman might not understand what it means for a place to be overrun. What it often comes down to is poop. With Escalante’s newfound fame and shrinking budget, cleanup is left to locals. Spalding says, “We all hike with lighters so we can light other people’s toilet paper on fire.”

It was 8:20 A.M., and I was cruising the Delicate Arch parking lot, which had already reached capacity. It did my heart good to see the hordes of Type A bucket listers, zipping off their pant legs, haloed in the sunrise mist of aerosol sunscreen. Even as I chafe against crowds, I believe these people will go home improved, rejuvenated, inspired, and perhaps even willing to vote for congresspeople who might increase funding for the parks.

But also: this mob scene was nothing like the Mighty Five commercial.

I headed on to the Fiery Furnace for my guided ranger hike. Amid the chaos, the park has managed to maintain a sense of quiet. We wound through fins and alcoves, taking time to view fox tracks and a black widow tucked into a crack. It was lovely. A part of me hated making a $16 reservation, when 25 years ago my friends and I clambered through here unregulated and inebriated in the middle of the night. But it’s like rafting the Grand Canyon: so precious that you may only get to do it once or twice in your life, and the planning and red tape is worth it.

My group contained a trio of Utahns from the suburbs of Salt Lake, an older man and his grown sons. They own a home in Saint George and have been hiking the Zion Narrows and other classics in the Mighty Five all their lives. One of the sons thought Zion had been overrun. “The state should stop advertising,” he said, “or at least give some truth in advertising.” The magical thing the Mighty Five advertises is solitude, but unless you’re able to visit midweek during the school year or in the dead of winter, you won’t find that in the parks. When we emerged from the Furnace, a ranger informed us that because every parking place was full, the park’s entrance was closed.

Although the Mighty Five parks are too crowded, I wouldn’t say they’re ruined. Last summer I was in Zion on a busy weekend. With 4.5 million annual visitors, Zion is by far the most packed of the Utah parks (and was the fourth most visited U.S. national park in 2018). This is largely because it sits within a seven-hour drive of 20 million Southern Californians. The horror stories about the lines and the crowds are all true.

But I had a blast.

Twenty years ago, the park made the visionary decision to shut Zion Canyon to cars. Everyone leaves their cars at the visitor center, the campgrounds, or the town of Springdale and takes a shuttle to the trailheads for Angels Landing and the Narrows. So there are no traffic jams, no motor homes circling for a space. From the tops of the sandstone cliffs, the valley below is silent.

Better than any front-country park in the entire nation, Zion has realized Ed Abbey’s dream of carlessness: “You’ve got to get out of the goddamned contraption and walk,” he pleaded, “better yet crawl, on hands and knees, over the sandstone and through the thornbush and cactus.” At Zion, though I was rarely less than ten feet from another human, I didn’t have that soul-sucking “park experience” endemic to Old Faithful in Yellowstone or the South Rim of the Grand Canyon, the feeling of inching forward on asphalt, then shuffling in a herd a few hundred yards to a vista, only to return to the confines of the car. I never saw so many fit Americans concentrated in one place, bedecked with hydro packs and hiking poles and amphibious footwear, hustling at the crack of dawn to hike ten miles with steep exposure, risking heat stroke and hypothermia in the same day. Despite the crowds—no, because of the crowds—Zion still feels like a celebration.

As Grand County’s Kevin Walker pointed out, national parks are built and managed to handle people, and despite the continuous budget cuts over the past two decades, they’ve done a good job of it, even if the only solution at Arches, for now, is to simply shut the gate. What’s more concerning about Utah’s ad blitz is the effect on the Insta-famous canyons—and their surrounding communities—that don’t have a gate rangers can shut.

When I asked Varela about the accusations that advertising is ruining canyon country, she said, “That is contrary to everything I stand for as a resident of this state and one who also wants to build a tourism economy. If you contrast the tourism economy with other ways to make a living in Utah, it is more sustainable.”

To be fair, Moab’s growth has its upsides. The schools and pools and bike paths are better now. The new housing stock is an improvement over the dilapidated trailers left from the mining era. Dine-out options used to be mostly burgers, but you can now get sushi, pho, and pad Thai—all on the same block.

And just as Moab has been hit hardest by the advertising, it has been the most assertive in fighting to preserve itself. Last year both the city and county passed moratoriums on construction of new hotels or overnight rentals. The city banned single-use plastic bags, which had begun to litter the scenic drive to the landfill. In what could serve as an example to the state Office of Tourism, the county’s tourism board has tried to shift the money raised by its local hotel tax away from advertising and into building infrastructure and educating visitors with its new Do It Like a Local campaign, which teaches etiquette like “don’t bust the crust” (when hiking or biking, stay on marked trails to avoid destroying microbiotic soils) and “respect the rocks” (stay off rock formations and don’t touch Native American rock art, which can be ruined by oils from your skin). In 2017, Moab elected a new mayor, Emily Niehaus, who was previously a ranger at Bryce Canyon and founded a nonprofit that helped low-income people build and own straw-bale, solar-powered homes.

As one salty Moabite summed up the new campaign: “They ruined the parks, and now they want to ruin the places in between.”

But the town’s attempts to turn back the state’s pro-business agenda are in limbo. One of Niehaus’s first duties as mayor was to travel to Salt Lake City and defend Moab’s new laws from an at times skeptical, if not downright hostile, legislature. When Moab banned plastic bags, a legislator introduced a bill that banned cities from banning bags. A state law demands that the county spend 47 percent of its hotel tax to promote tourism. Meanwhile, the ban on new hotels is under scrutiny. The governor has warned against of the rise of “socialism” in places like Grand County.

This same pro-business view seems built into the Office of Tourism, too. The governor’s Board of Tourism Development, which oversees it, consists of reps from the lodging, restaurant, car-rental, and ski-resort industries; notably absent are federal land managers, environmentalists, or advocates for affordable housing. Lance Syrett, the chairman of the board, owns hotels that have boomed since the days of the Mighty Five campaign. The budget for the Office of Tourism is incentive based, too: if tourist-related tax revenue increases 3 percent in a year, the office can receive an additional $3 million from the legislature. (However, Syrett told Outside that the incentive agreement is nonbinding for the state; there have been years when his office did not receive additional funds, even when taxes from tourist-oriented goods and services increased by more than 3 percent.)

But who in southern Utah benefits from this growth? Clearly, the owners of restaurants and hotels and rental cars, some of whom are local residents while others are out-of-state corporations. Workers get jobs, but these tend to involve seasonal service work, with low wages that are eaten up by exorbitant rent. Return visitors and residents alike find their favorite places teeming with crowds. As for the office’s claim that each household gets a $1,200 to $1,300 tax break from tourism revenue, that’s mostly true but also misleading. It assumes that if tourism suddenly evaporated, the state would not trim its budget to fit the dried-up revenue stream. Syrett surprised me with this little-known fact: in terms of gross revenue, the city that has profited most from the Mighty Five campaign is not Moab or Saint George or Escalante. With its international airport, car-rental companies, and airport hotels, it’s Salt Lake City.

For such a petite person, Mayor Niehaus commanded a withering glare. During my Labor Day visit, I met her and her ten-year-old son, Oscar, at their house for breakfast, where she scrambled eggs with onions, garlic, and herbs. “Everything you’re eating was grown in the yard,” she told me. As I was finishing my eggs, she peered over and said, “Does Outside magazine understand the irony of looking for the villain of the degradation of red-rock country? Outside magazine, along with Instagram and the Mighty Five ads, are the top reasons this place is crowded.”

“Did you put hot sauce in this?” I sputtered. When I first started writing for outdoor magazines, my Moab friends threatened me with banishment and beatings if I ever revealed secret spots. A few years later, when I lived in New York, a publication like this one solicited a few Moab tips. I’d like to say that I stood tall and refused it—or at least that the price for my soul was high. But I really needed the $600. I resolved to write the thing but to only send people to the national parks and locally owned businesses. I called one of the local bike-tour operators, and before I had a chance to explain my good intentions, he hissed, just before hanging up, “Your magazine sucks.”

A tour operator may lack claim to the moral high ground, but nearly everyone who lives in southern Utah loves it as it is—and also wants to earn a living. Whether your job here is cook, waiter, miner, rancher, ranger, or telecommuter, your very existence will in some way change the thing you love. We all bear some responsibility in changing this place.

Yet we don’t bear it quite evenly. Market forces and shifting demographics and social media don’t deserve the same sort of scrutiny as taxpayer-funded programs like the Office of Tourism. And the more I learned, the more I became convinced that these initiatives may actually hurt the taxpayers who are paying for them.

Syrett likened what was happening in Garfield County to an oil boom, with 47 percent of jobs related to tourism, more than any other sector. And most booms are followed by bust. Early numbers indicate that 2019 was another flat year for Utah national-park visitation, or maybe even a decline.

“All these businesses have popped up now because of the Mighty Five, and there’s a bit of a panic,” said Syrett. “We’re in a free fall.” According to him, small towns in Utah are clamoring for more ad money for their areas. It’s easy to see how a cycle of taxpayer dependence is born. The state advertises, the hoteliers build, the rooms aren’t filled, the owners demand more advertising, and so on.

I asked Syrett, “Is it government’s role to bail out these entrepreneurs who made risky investments?”

He let out a patient laugh. “Well, we can debate that all day long. The small rural communities that surround the Mighty Five destinations have been desperate for economic development for so long, that you can’t judge them for being excited for the investment in their communities. Were there some planning mistakes made? Sure, but the investment has been welcome.”

I was fascinated by the Office of Tourism’s “addressable” TV strategy. After years of crunching data, Varela’s team has divided her audience into four personas. Achievers, who favor personal challenge, are served images of mountain biking and rock climbing on television and social-media ads; explorers, who seek unique personal experience, see slot canyoneering; families, who wish to give their children an unforgettable journey, see a child trout-fishing with dad; and repeat visitors, who want the off-the-beaten-path experiences and locations they missed the last time, see Navajo weavers.

While this sort of opus analytica represents the pinnacle of travel marketing in the era of Big Data, it also turns my marrow to ice. At the risk of revealing my age, I’ll say that, in the old days, if you wanted red-rock magic, you followed these steps:

- Engage in hitchhiking.

- Insert intoxicants in your mouth.

- Misplace the map.

- Break down on a dirt road.

- Start walking.

Now when the recipients of these addressable ads ride that sandstone rim on their mountain bikes, or squeeze through sheer red narrows, it might be because marketeers collected their clicks and coded that dream for them.

It’s a well-worn chestnut that wilderness isn’t just a cool trip but a type of freedom, essential to democracy and the soul. In nature, we free ourselves from the world’s day-to-day moneygrubbing and conformity. In creation we find Creator. But what if freedom is a commodity packaged by advertisers? When our dreams are concocted by focus groups to maximize what we spend on VRBOs and craft brews, that old Guided by Voices anthem rings in my head: You can be anyone they told you to.

It may be tempting to blame the marketeers, but they are simply carrying out orders from a governor who has a history of pushing to develop public lands for revenue. In 2012, Governor Herbert demanded that the federal government hand over 30 million acres of public land to the state. He excluded the five national parks from his scheme but included the monuments, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, the national forests, and millions of acres administered by the Bureau of Land Management. Herbert hasn’t explicitly stated what he would do with those lands—he frames it as a states’ rights issue—but precedence hints at how Utah might manage them, given the chance. The state already owns 3.4 million acres of trust lands, which it has decided not to “preserve and protect,” as with the national parks, but commercialize. These lands were deeded to Utah when it entered the union in 1896 but were generally left undeveloped until 1994, when the legislature created an agency that would assertively raise revenue on them. Projects include a 40,000-person artificial-lake subdivision in the desert near Zion. Outside Moab, over the howls of locals, the state is developing a 24-hour truck stop and, at the base of the Slickrock Trail, a 150-room four-star hotel with a convention center, 150 rental “casitas,” and 43 homes.

In 2008, the Utah legislature passed a law allowing off-road vehicles on all dirt roads, including those in the Mighty Five. This was another effort to buck federal control over state lands—ATVs have typically been prohibited by the National Park Service. The NPS resisted for a decade, but in September, after another round of pressure from Utah lawmakers, it caved. The advertised epiphany of biking under the vast skies of Canyonlands’ White Rim Trail would be updated with the high whine of ATVs.

Within a month, after a chorus of outcry, the NPS backtracked. Now the decision is in limbo. It remains unclear how long the Mighty Five will maintain their wilderness character when battered by Utah’s agenda.

I drove south from Moab into San Juan County, which contains a portion of Canyonlands as well as three of the campaign’s “in between” spots: Bears Ears, Goosenecks State Park, and Monument Valley Tribal Park on the Navajo Nation. I crossed the Ute Mountain Ute Reservation at White Mesa. Until a recent federal court action, a white minority ruled over the Native majority here. The county officials despised Bears Ears, while the tribes supported it. Before being voted out in 2018, the county commission stuck its citizens with a half-million-dollar legal tab, paying an out-of-state attorney $500 an hour to thwart Obama and the tribes.

Maybe complaints like mine are just a lot of pissing in the wind by white people who, if we really want to know what it’s like to be pushed off the land by newcomers, should go talk to an Indian. True. Yet the forces of history that stole the continent from Natives are similar to those that now sell it. The machinery of civilization churned across the West, slayed the buffalo, dammed the Missouri and the Colorado and the Green and the Columbia—and will next gobble up our world’s most precious commodity: solitude. What society needed then was land and timber and buffalo hides, and it took them. In the 20th century, it needed water and electricity, so it stopped the rivers. Now it needs Mystery and Mystical, and it will advertise and sell them until they’re gone.

So which are we: The boy crying wolf about a land that will nurture us no matter what? Or the frog in the pot, unable to sense how bad it already is? I don’t want to just be a curmudgeon who mourns the passage of time, who fights any change to the landscape because conceding change concedes my own mortality. I will never be young again, I get that. But maybe, if the sorrow of human life is our inevitable death, then one way we tap into the eternal is to see how that which is not made by our hand will outlast us all, just as it preceded us.

In nature, we free ourselves from the world’s day-to-day moneygrubbing and conformity. In creation we find Creator. But what if freedom is a commodity packaged by advertisers?

Shortly before crossing into the Navajo Nation, I stopped at Goosenecks State Park, which pretty much defines being in the middle of nowhere: the places it’s in between are Bluff, population 320, and Mexican Hat, population 31. I hadn’t been here since 1990, my very first trip to Utah, five of us longhairs in a VW camper van emitting puffs of “wow” and “holy shit” as it bounced over red washboard roads. Now I bumped along that plateau of sagebrush and juniper, paid five dollars at a booth, and there, amid a smattering of picnic tables and outhouses, peered over the rim into the staggering canyons of the San Juan River.

The place looked unchanged. A Native woman sold silver jewelry beneath a tarp. It was Labor Day and—ad blitz notwithstanding—only nine cars had found their way here. A child gazed down at the green river meandering a thousand feet below, a million years away, and said, “I want to go swimming in that pool.”

By doing just about nothing here, the state appears to have done it right.

The Office of Tourism likes to brag that, anywhere else, its state parks would be national parks. Maybe. But as I looked around and found no trails, no rangers, nowhere to go other than this dirt lot, I wondered if this “park” might more accurately be called a scenic overlook or a campsite. The Goosenecks were briefly enveloped by Bears Ears, and after the cuts to the monument, the state has proposed to construct mountain-bike trails on the no-longer-protected desert. Do humans need to change this landscape, to make it more attractive, more fun?

With talk of “destination development” and “destination management,” civilization forges ahead, until one day this chest-clenching slab of infinity, this windswept monument to nature’s indifference, these eternal deep twists of snowmelt in dubious search of the sea, will cease to be sacred—and will become a Brand.

I hope to God it fails.

Lead Image: Art by Petra Zeiler; PhotoQuest/Getty (Arches); Philippe Beyer/EyeEm/Getty (people)

Editor’s Note: The story has been updated to clarify Lance Syrett’s views.