Listen to a conversation about this story with author Abigail Covington and publisher Michael Shapiro on the Delacorte Review Podcast.

The president of Washington and Lee University, Will Dudley, understood the depth of his problem the moment he turned on the television and saw hoards of white men in collared shirts and khakis carrying tiki torches as they marched through Charlottesville, Virginia, protesting the removal of a statue of Robert E. Lee.

For nearly 150 years, the school over which he presided managed to avoid any controversies related to its namesake and former president. But with the August 2017 white supremacist rallies and riots in Charlottesville, Virginia and the reaction of President Donald Trump — “You also had some very fine people on both sides” — had come new and, in some quarters, unwelcome scrutiny over the enduring presence in the south of memorials to the Lost Cause. And nowhere was that presence more deeply ingrained than in Lexington, Virginia on the campus of Washington and Lee, at whose spiritual core sat the memorial chapel in which lay in eternal repose the remains of one Robert E. Lee. Unlike any of his predecessors, Dudley understood that this time he’d have to deal with the school’s Robert E. Lee problem. He believed he had a path toward a solution, and that it began with Ted DeLaney.

“No one has a more penetrating sense of W&L’s history and character than Professor DeLaney,” wrote the school’s provost Marc Conner in W&L’s official magazine The Columns. Now 75 years old and semi-retired, DeLaney grew up in the black neighborhood of a then heavily-segregated Lexington and has a relationship to W&L unlike any other. He started as a custodian in the early 1960s and spent twenty years as a lab technician in the school’s biology department. He then enrolled as an undergraduate, graduating cum laude in 1985 at the age of 40; he later returned as a professor in the history department where he taught courses on such subjects as Comparative Slavery in the Western Hemisphere, African American history, Civil Rights and Gay and Lesbian history.

President Dudley’s post-Charlottesville plan was to form a commission whose unenviable task would necessitate separating the myths of Robert E. Lee from the facts of his life. It would gather opinions on Lee and his legacy from the W&L community, whose constituents often contradicted each other. “W&L is a fortress of white privilege,” one alumnus would seethe during an open conference call for the school’s graduates hosted by the commission. Another would lay out the stakes in clear and troubling terms: “If the president and the board don’t heed the final recommendations of the Commission, the university will attract tourists like Dylan Roof.”

The commission would have twelve members, drawn from W&L professors, faculty, current students, and alumni. More than examining the connection between Lee and the school, Dudley wanted recommendations on ways of restructuring the Lee narrative in the wake of the nation’s renewed attention to race, history and justice. He asked Ted DeLaney to join it, and DeLaney quickly agreed.

In many ways, DeLaney’s life had been preparing him for this moment. For over thirty years, he’d wandered in the shadows cast by Confederate monuments and statues in his hometown. He’d attended convocations and welcome addresses at Lee Chapel and sat in pews built atop Robert E. Lee’s family crypt. His tolerance had been tested and fortified by each indignity he’d silently suffered and every display of hagiographic admiration he’d witnessed his friends, colleagues and students display toward Robert E. Lee. He was both fired up and exhausted; reluctant and motivated to finally take on the legacy of a Confederate god who’d haunted him all his life.

*

Robert E. Lee’s relationship with W&L began in 1865. Astride his beloved horse, Traveller, the Confederate general rode into Lexington to assume the presidency of the financially destitute Washington College, just weeks after surrendering at Appomattox. It was the second time since its founding in 1746 that the school, which had originally been named Liberty Hall Academy, teetered on the brink of ruin. On the first occasion, in 1796, George Washington saved the school by giving it $20,000 worth of James River Canal stock. To express their gratitude, the trustees changed the name of the school first to Washington Academy. When its status was later elevated it took the name Washington College.

Lee took the job with reservation: He worried he “might draw upon the college a feeling of hostility.” Nevertheless, he accepted the role so that, away from the battlefields, he could continue to educate the young men who had borne the burden of the war. Southerners rejoiced. The Richmond Whig gushed over the general in their reporting of the news: “And now that grand old Chieftain…betakes him to as noble a work as ever engaged in the attention of men.”

The dilapidated college began to flourish under Lee’s tenure. Virginians, in honor of Lee, poured money into Washington College. By the end of his five-year term, the school’s endowment was double its pre-war size. Ever mindful of education’s pivotal role in creating successful societies, Lee incorporated the nearby Lexington Law School into the college and created courses in journalism and business that eventually led to the founding of the School of Commerce and the Department of Journalism and Mass Communications. These courses in business and journalism were the first to be offered in colleges in the United States, leading Lee to be credited with helping establish the modern university curriculum. Even more important to Lee was the principle of honor, which was codified by the only rule he ever imposed upon his students: Always be a gentleman.

Robert E. Lee died at age 63 at 9:30 am on October 12th, 1870. By 9:40 am, classes at Washington College were suspended and stores were shuttered. The townspeople poured into Lexington’s cobblestone streets. In Richmond, officials declared it a day of mourning. Virginians were overwhelmed with grief. Thousands attended Robert E. Lee’s funeral. Now had this been any other beloved college president, the story might stop here. But admiration for Robert E. Lee stretched far beyond the soft-topped mountains of western Virginia. It extended down throughout the delta and east to the bombed-out forts that dotted South Carolina’s coastline. So it was those southerners too, not just the college students, who were left reeling after the death of Robert E. Lee. In the absence of his physical presence, Confederates everywhere craved a legacy and a philosophy, if not a religion, they could cling to that would assuage their grief and guilt over sending thousands of their own men to fight an avoidable battle they knew they’d most likely lose.

Lee’s widow Mary Anna Custis Lee recognized that need and sought to satisfy it by dedicating her remaining years to the establishment and preservation of Robert E. Lee’s legacy, both on W&L’s campus and throughout the south, having once famously declared her husband to be “the hero of a lost cause,” whose “martyr” blood was shed for his country.

It was a term she’d borrowed from Virginia journalist Edward Pollard, who in 1866 published a book justifying the Confederate war effort entitled The Lost Cause: A New Southern History of the War of the Confederates. It was the first piece of what would soon become many that presented the Confederate’s cause as a noble one and its military leaders, especially Lee, as saints. The Lost Cause was built on certain core ideas: Secession, not slavery, caused the Civil War; enslaved African Americans were loyal to their masters and the Confederate cause; the Confederacy’s defeat was due to the Union’s overwhelming advantage in numbers and resources, not its military strength; Confederate soldiers were heroic and virtuous, and southern women were sanctified by the sacrifices of their loved ones.

Many northerners and unionists protested the Lost Cause’s glorification of the Confederacy and soft-pedaling of slavery, but southern sentimentalists overwhelmed them, and the Lost Cause narrative prevailed as the primary lens through which people from the south thought about and remembered the Civil War era. As time ticked forward, the Lost Cause’s influence spread. The fear that Yankees might torch the southern way of life during the Reconstruction era fueled the movement and by the mid-20th century what had started off as rose-tinted recollections with Lee at the center ended up as text in school books with the general cast as a hero. One such book was Charles Flood’s Lee: The Last Years. And despite it being discredited by serious historians as nothing more than Lost Cause propaganda, it was given to incoming W&L freshmen up until the very recent past.

This is what Ted DeLaney was up against: one hundred fifty years of purposefully misleading history stuffed inside the minds of his students and their parents and their parents’ parents. To detach them from all that they knew would be an enormous task — one that DeLaney had spent years both engaging with and retreating from, careful to never ask too much of anyone at a given point. If Lee’s relationship to Washington & Lee was about leadership, DeLaney’s was about deference. Fortune didn’t favor the bold at W&L, especially if you were an outsider. And simply by the color of his skin–despite being born and raised in Lexington and having spent his adult life on the W&L campus–DeLaney remained an outsider.

*

In the fall of 2017, I sent Ted DeLaney an email requesting an interview about the commission and his role within it. He responded curtly: “I will not speak either on or off the record.” But like linen, he’d soften over time. With some encouragement and assurances that response transitioned into this: “This is a very difficult process, and it needs to be an in-house only conversation as much as possible.”

And then finally this: “I will gladly chat with you. My basic concern is that you understand that I will represent only my views, and the most important of those is that the W&L narrative is honest and that the community accepts and owns it. There are some troubling aspects of our history and General Lee’s history that are not part of the public narrative.”

Attached to that email was an unsolicited reading list including Alan Nolan’s Lee Considered; Emory Thomas’s Robert E. Lee: A Biography; Elizabeth Brown Pryor’s Reading the Man, and Olinger Crenshaw’s General Lee’s College all of which he expected me to read, alongside a few additional papers from various academic journals, ahead of our meeting a month or so later in Lexington.

The day I arrived in Lexington in January of 2018 a cold front had frozen the town to a standstill. Frost blanketed the hibernating hydrangea bushes while ice on the streets kept most of the city’s residents inside under the covers. Except Ted DeLaney. Despite the chill, he was fired up. He’d requested we meet at 8 am outside of his office. I arrived at 7:55 am only to find him already outside and waiting for me. We were going to walk all over the campus of Washington and Lee, starting in front of the history building, one of five buildings that lined the rim of the school’s great front lawn. The unspoken purpose of this tour was to provide evidence for a claim he made in an email to me: that “W&L is unique because the entire campus is a Confederate monument.”

“Now let’s look at the back of that statue,” DeLaney said as we hustled across the lawn to examine a bronzed man standing on top of a tall rectangular block. On W&L’s campus, it’s easy to assume that anything that’s been memorialized is somehow associated with Robert E. Lee, but in this case the man being honored was Cyrus Hall McCormick — a native of Rockbridge County who invented the reaper which made harvesting so much easier for farmers in the breadbasket of the South. I gleaned this information from the block of text placed on the front face of the rectangle Mccormick stood upon.

The information was there for everyone to digest, but nobody ever did. Myth often trumps facts at Washington & Lee and students assumed that this statue, like others on campus, commemorated Lee, to whom McCormick did bear some resemblance. It happened all the time. One of DeLaney’s de-facto hobbies became convincing stubborn students that the statue wasn’t of Lee. He’d made $50 off a bet with a student that way. Right there under their noses it said Cyrus McCormick, but in the hearts and minds of the W&L community, everything always read Robert E. Lee.

Back inside the history building our meeting continued. Ted DeLaney’s office was taller than it was wide. Two floor-to-ceiling bookshelves spread across its right corner. A metal ladder he used to access his out of reach books rested on rails attached to the shelves. There was an enormous bag of soil behind his cherrywood desk that gave life to the half dozen plants asleep on his bookshelf. On top of the bureau by the door, a bobblehead of Barack Obama wobbled gently next to a statuette of Frederick Douglas.

“No figure in American history should be above historical analysis,” DeLaney told me as he fiddled with the Keurig machine stationed between us. “But when I started teaching at W&L,” he added quickly, “I knew I was at a place where Robert E. Lee was somehow at the same status as Jesus.” This meant he had to be careful. “I didn’t want to say anything that was going to possibly cost me my job.”

So DeLaney stuck to the script that no one had to give him and restrained himself from asking any obvious questions about Lee that “veered from the W&L narrative.” One of the most radical claims DeLaney made during his early years of teaching was, “the central moral issue of the 19th century was slavery.” Looking back on it now, the comment seems painfully quaint. “I mean, my God,” DeLaney said as if ashamed of his younger self, before remembering that he was simply saying, or rather not saying, what he had to in order to get by in a climate designed by elite, white southerners for elite, white southerners. “It’s called survival,” he announced poignantly.

Essential to a complete understanding of Ted DeLaney is an examination of his refined wardrobe. Each aspect of his clothing, from the pattern of his pocket square down to the fabric of his socks, is considered with his white colleagues in mind. “If I don’t put a coat and tie on then someone is going to assume I’m on the support staff,” he told me matter-of-factly. His preference for bowties over neckties is perhaps the most outlandish aspect of his wardrobe.

DeLaney wears khaki pants in the spring and summer and corduroy pants in the fall and winter. He doesn’t know exactly when all of his students started wearing sweatpants and hoodies to class, but if he could go back in time and prevent it from happening, he certainly would. DeLaney is also a sucker for a well-fitting navy blazer and a crisp, light blue dress shirt – the unofficial uniform of the well-appointed historian.

Equally appealing are DeLaney’s looks. Topping off at five feet six inches, he hardly cuts an intimidating figure. He has soft features: a polite but pillow-y beard, long, light brown lips and eyebrows that follow the soft arch off his perfectly round, wire-framed glasses. He’s bald but you wouldn’t know it because he never leaves the house without his herringbone driving cap. He’s as familiar looking to an upper-class southerner as a fine piece of Royal Doulton China and just as tasteful too.

Reflecting on his attire, I’m reminded of a story he once told me about a younger, disheveled colleague who jokingly claimed the only reason Ted dressed so sharply was to make the rest of the staff look bad. To which an unusually daring DeLaney replied, “I don’t have the white privilege to dress the way you do.”

“It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others,” wrote W.E.B. Dubois’ in The Souls of Black Folk. DeLaney cited the passage early on in our conversation, and looking back I see its relevance in many of the memories he shared with me that winter morning. All those times he’d bitten his tongue for fear of offending someone, how hard he’d worked to graduate cum laude, his clothes … it all stemmed from him considering himself from the perspective of a white man, asking questions like: How would a white person react to this? Would he respect me more or less for it? Would these cufflinks disarm him of his racial presumptions?

And yet in equal measure to DeLaney’s desire to garner respect among his white peers was his desire to live an authentic life as a black man. That’s perhaps why he never left the black neighborhood he grew up in, why he founded W&L’s first African American studies program, and why for many years he’d taught an immersive four-week course in which he drove a handful of students in a van through the southeast on a tour of significant Civil Rights destinations.

“I’ve never forgotten where I came from,” he said, delivering the words with a determination that suggested he was defending himself against accusations of neglect. ”I have a lot of love for the black past I grew up with.” Still, most of his days were spent “living in a white world where there’s very little diversity.” And when asked why he stayed in such a racially divided environment, his response was almost innocent in its simplicity: “This place is home to me.”

*

“There’s a story that resonates across this campus like crazy,” Ted DeLaney told me as we made our way toward Lee Chapel together during the final hour of the tour. “I’ve heard it so many times, I couldn’t even begin to count.” The story goes like this: Soon after the Civil War ended, a black man stood in St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Richmond and marched to the communion table ahead of the congregation. The white people in the church were outraged by his bold behavior until General Robert E. Lee himself walked down the aisle and reverently knelt down next to the man to partake in communion. Lee’s humility coaxed the other church members out of their seats, and there in the bright morning Sunday sun, blacks and whites prayed alongside each other in Virginia for the first time.

It’s a lovely story, but most historians don’t believe it ever happened. It first appeared in both the Confederate Veteran magazine and the Richmond Times Dispatch in 1905. It was then supposedly included in the original edition of R. E. Lee: A Biography by historian Douglas Southall Freeman. For years the book was celebrated, even winning a Pulitzer Prize in 1935, but it’s since been dismissed by contemporary historians as a work of hagiography. Still, it’s a story that many in the W&L community cherish and purport as evidence of Lee’s outstanding character and benign treatment towards African-Americans.

“If the story’s been so thoroughly discredited and debunked, then why do people go on repeating it?” I asked DeLaney as he held the door of Lee chapel open and ushered me inside.

Keeping his hands planted in the pockets of his corduroy pants, DeLaney shrugged his shoulders all the way up to his earlobes. “Beats me,” his eyes seemed to say. It was the look of a man who’d grown almost comically tired of asking himself the same question for years.

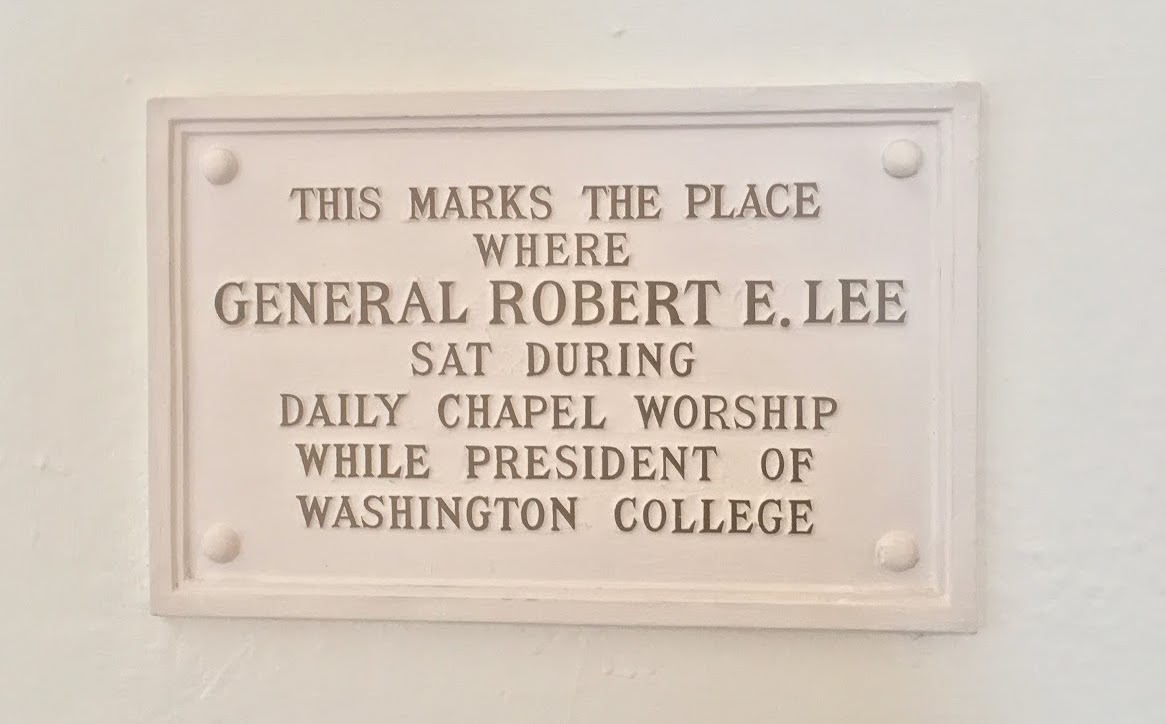

We turned the corner and stood at the back of the pews. The winter sun warmed our skin as the bright afternoon light flooded the chapel’s giant windows, transforming its eggshell white walls one shade whiter. Cramped rows of white and almond-brown pews, divided neatly into three sections by two aisles, filled the bulk of the chapel’s ground level. Above us, a horseshoe-shaped balcony supported by four columns stretched across the back third of the chapel. A dozen bronze and marble commemorative plaques lined the chapel’s walls. Scored into them were dedications to deceased alumni, like Livingston Waddell Houston and Kiffin Yates Rockwell. Above the first pew and bolted into the chapel’s right wall, a few inches above the inside seat, rested the most important plaque, which featured text written in angular, gold, capital letters: THIS MARKS THE PLACE WHERE GENERAL ROBERT E. LEE SAT DURING DAILY CHAPEL WORSHIP WHILE PRESIDENT OF WASHINGTON COLLEGE.

It was the subtlest of the three out-loud references to Lee contained within the chapel. One of the others, a portrait of a smiling Lee dressed in his Confederate uniform, stared at the back of my head from across the room. Situated on the left side of the chapel’s platform, the portrait had been hung so expertly it looked as though it was hovering in front of the wall which existed solely to lend support to the portrait.

A spotlight from above produced a cone of amber light that caked the portrait in a glow. It looked priceless, and the original is. But this wasn’t the original. Instead, a copy. After the riots in Charlottesville, the original was put in storage to protect it from potential harm. So was the portrait of George Washington whose copy was displayed in a similar manner to Lee’s and featured on the wall opposite the platform. Despite their impressive staging, the portraits paled in comparison to the statue of Robert E. Lee that was nestled between them.

The recumbent Lee, as the marble memorial is known, is a life-size rendering of Robert E. Lee dressed in his Confederate fatigues positioned to reflect him napping in a battlefield. The piece was commissioned by Mary Custis Lee and brought to life by the sculptor Edward Valentine of Richmond. At the height of Reconstruction in 1883, the memorial was revealed and instantly became a shrine to the Confederate cause. Since then flocks of southerners have traveled to Lexington to pay respects to the Confederate hero, who lying in state, resembles a recently deceased pope or the sleeping knight effigies of the Crusaders. And therein lies the problem—a mortal man given the treatment of a saint. “The symbolism there is a violation of the first commandment!” exclaimed DeLaney during our tour. Robert E. Lee — the false God of the Confederacy.

The Lee Chapel, the recumbent Lee and what to do with them were at the heart of the commission’s work. They embodied every nuance of the difficult question Ted DeLaney and the rest of the commission had been tasked with answering, which was essentially: In the post-Charlottesville era, when Confederate iconography is more divisive than ever, should Washington and Lee at long last distance itself from Robert E. Lee?

And to that question, there were many, many answers.

“We don’t have any conversations about whether or not Robert E. Lee was a racist,” groaned Dannick Kenon, a junior from Long Island. “All we have is a church that’s named after him that we have to go as freshmen to sign a white book.” Kenon was one of many students of color I spoke to who felt either unhappy, uncomfortable, unwelcome or some combination of all three in reaction to the W&L’s historical cozying up to Robert E. Lee. To Kenon and others, Lee’s contributions to W&L did not counterbalance his legacy as a Confederate hero. And they were all keenly aware that for as much as the school made of Lee’s outstanding character, they would’ve never been on the receiving end of his benevolence or integrity. Because they were black and, as then junior and commission member Elizabeth Mugo put it, “Lee probably didn’t have a student like me in mind when he rebuilt this university.” What he’d had was slaves, up to thirty of them at one point, and that had become increasingly impossible to ignore.

“Whenever I hear Robert E. Lee’s name, I’m always thinking about how he had slaves,” said Mubi Adeliyi, an African-American junior. “Before Charlottesville, I never thought about that.” Adeliyi’s pre-Charlottesville selective memory was most likely a byproduct of the benign neglect approach W&L took towards memorializing Lee. “Memorializing him in the way that we do, without accepting all of the problematic stuff, allows people to ignore certain characteristics of Lee’s,” Adeliyi said. Which in turn made Lee easier to revere, more difficult to let go of, and, if you’re a white, southern man of a certain age, almost impossible not to defend.

Or, as Cynthia Cheatham, an African-American member of the commission and an active W&L alumna told me, “I don’t think anyone talks about Robert E. Lee in the way that W&L folks do.”

They begin by listing his contributions to the university— as I heard when I headed over to the cafeteria and began accosting students about their views of the general.

“As a school, we have so much to thank him for, like adding the first journalism program and expanding the science and math departments,” mumbled Ryan Brink, a white student dressed in brown khakis and a pale yellow, collared polo shirt. “We really only talk about what he did for W&L.” In his words, demeanor and attire — pale brown khakis — Brink was representative of so many W&L students in that he while he was comfortable discussing Lee’s contributions to the university he began to stumble over his words and craned his neck in search of excuses to break away from our conversation when I asked if he thought Lee was racist.

If Brink was uncomfortable, alumni I would quickly learn were not. “They believe he’s an honorable gentleman that answered the call of duty and then saved their college from extinction. Boom. End of story,” insisted Beau Dudley (no relation to the college president) executive director of the alumni association and commission member.

Not only were some of the alumni set in their ways, some stubborn beyond redemption even, (“I don’t even know how someone can be that set in his ways,” said Cynthia Cheatham, “and I’m Catholic!”) they were also influential. As the primary donors to the school’s endowment, their opinions had to be handled delicately. And in Ted DeLaney’s case, that meant, once again stomaching comments such as “[the university] should resist the trap of chasing the diversity of a jelly bean jar,” and many others just like it on one of four open conference calls hosted for the alumni.

The commission spent eight months researching and reaching out to various community members. And when this phase of their work was complete two contradictory points had become as clear as a priceless family diamond: One–the school’s overt glorification of Robert E. Lee made many students, teachers and staff members uncomfortable; and two–there was a plurality of important alumni who would not tolerate any changes to the school’s campus and treatment of Robert E. Lee. Making things all the more anxiety-inducing for the commission were the unknowable consequences of their recommendations. Would donations plummet if the school chooses to transfer ownership of the chapel to an independent group? And if so, would that affect the school’s ability to offer scholarships to low-income students? On the other hand, if in the post-Charlottesville era the commission suggested that W&L continue to publicly celebrate its relationship with Robert E. Lee, what would that say about the school’s priorities?

As noted historian and author of Antidote to Revolution: African American Anticommunism and the Struggle for Civil Rights Jelani Cobb put it: “Does saving a university really counterbalance the act of owning other human beings?”

*

In May of 2018, the commission answered Cobb’s question: No, it does not. Months of research, eight meetings with W&L law and undergraduate faculty, sixteen meetings with university staff members; four telephone sessions for alumni totaling more than 400 alumni listening in or speaking, plus nine meetings with current students, and the commission was finally ready to submit its formal suggestion to president Dudley and the Board of Trustees: “Now is the time for Washington and Lee to take action.”

Tucked within that overarching recommendation sat thirty-one additional ones ranging from the modest–“Release the commission’s report in full to the university community and post on the website”–to the controversial–“Convert Lee Chapel and Museum building into a museum, which would serve as a teaching environment with a well-appointed classroom, offices, and state-of-the-art exhibition space… The new University Museum would no longer hold any university functions.” To some, this recommendation, the eighteenth, registered as a death knell, the beginning of the undoing of W&L as an elite, conservative, and proudly southern institution of higher education.

In describing this recommendation and others related to the chapel, Hayden Daniel, then editor of Washington & Lee’s student-run conservative magazine The Spectator, wrote “These recommendations … represent an existential threat to the traditions and history that make Washington and Lee University a unique and venerable institution.” Even the commission’s careful marshaling of evidence for each of their recommendations did little to convince the most stubborn dissenters like Daniel of the necessity of the proposed changes. The tenth recommendation, which called for the relocation of the signing of the Honor Book, stemmed from multiple students and faculty members expressing their discomfort in having to endure such events in Lee chapel, to the extent that some of them simply don’t go. Daniel described this recommendation as a “malicious and unrelenting assault on Robert E. Lee and his legacy.”

Other suggestions caused much less controversy but were equally important to Ted DeLaney, whose most humble plea had always been for W&L to use its monuments and history as a teaching opportunity. Out of the thirty-one recommendations the commission made, nearly half of them called for an increase in efforts and funding for the ongoing exploration and dissemination of the school’s history among its community members. Chief among those recommendations was a brainchild of DeLaney’s: “Require each undergraduate student to take a seminar that explores W&L history, including the involvement of the namesakes, the contribution of enslaved persons, the role of W&L in the creation and dissemination of the Lost Cause narrative.”

*

Nine months had passed since the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville and President Dudley’s understanding that something had to be done if his school was to address the moment and the enduring and ever angrier (and now deadly) battle over the Lost Cause. He had taken the safe path–forming a commission–and the wise one in asking Ted DeLaney to join. For all of DeLaney’s skill at adapting to the white milieu in which he had thrived, there was no doubting his views about the past, the confederacy and the legacy of Robert E. Lee and the Lost Cause. DeLaney and the commission would give Dudley cover, that is if he chose to act.

I knew something about the legacy of the Lost Cause. I’d grown up in North Carolina in a sociable family and consequently ended up at the kids table at lots of dinner parties, cocktail parties, country club dances and corporate fundraisers. Wandering around those politely decorated rooms, I’d witnessed aging husbands and wives (or second wives), tongues softened by wine, tell sentimental stories about their beloved homestates of Georgia, Virginia, South Carolina, North Carolina, even the east-coast adjacent Tennessee.

Subtle as it might’ve been, embedded in all those stories were traces of Lost Cause history and evidence of the current south’s ties to the antebellum south. Maybe the person telling the story was named after his great-great-grandfather who happened to fight alongside Lee during, well, any number of battles. That happened all the time. Or maybe the textbooks used in the high school where a proud father was once the student body president taught a sanitized history of the slave trade. Odds are it did. It was so easy to sit back and judge my parents’ friends. As the gay daughter of two diehard Democrats, I figured myself worlds apart from the seersucker-wearing good ol’ boys I’d often run into at the yacht club. But Lost cause history was in me too.

All I’d ever been told about my middle name Stedman was that it was a family name. Some great, great uncle from my Dad’s side was a celebrated colonel in some war. When I eventually did my own research I discovered that the man I was named after, Charles Manly Stedman, was a decorated Confederate major in not just any war but the Civil War, leading North Carolina’s 44th North Carolina Infantry. After the Civil War he was elected to Congress and in 1923 he introduced what’s now referred to as the “Mammy Monument Bill” which called for the construction of monuments to slaves who remained faithful out of “love of masters, mistresses and their children” throughout the south. That bill passed the Senate but was thwarted in the House due to large-scale protests from African Americans.

Good intentions can’t spare southerners from our history. Nor could a holier-than-thou attitude towards my more conservative acquaintances undo my own DNA and twisted history with the Confederacy. Unfortunately, we all read the same textbooks. And learning from the Lost Cause that our ancestors’ purpose was a righteous one and that Robert E. Lee lived without sin, allowed us to avoid engaging in a difficult discussion about how the ways we honor our ancestors might hurt or offend others. Things we hoped time would solve, like racism, resentment and civil rights violations, have resisted erosion and only gained strength from our complacency. Talking to Ted DeLaney over the course of two years taught me that Lost Cause history wasn’t just some toothless doctrine. It was a designed crime against black humanity and ongoing inaction that only added insult to injury. I suppose that’s why, despite having no allegiance to W&L, I still hoped President Dudley would heed the commission’s advice and begin to undo the school’s centuries old tradition of harmful neglect. It felt like the least they could do.

*

On August 28, 2018, just over a year after President Dudley announced the formation of the commission, he thanked them for their work and dutifully responded to various clusters of recommendations, expressing broad support for the commission’s ideas for new educational initiatives that sought to tell a more complete version of W&L’s history. In one instance he explicitly agreed with the commission and committed the university to acting upon their recommendation to hire a director to oversee the presentation and management of W&L’s institutional history.

But as to what to do with Lee chapel and the Recumbent Lee, the issue that had originally ignited this debate and sucked the oxygen out of every room on W&L’s campus for an entire academic year, the commission and President Dudley stood at odds. Ted DeLaney and the other members had expressed their vision clearly: Convert the chapel into a museum and build a new space to house important institutional events. And in response President Dudley was equally clear: “We can and will continue to use Lee Chapel, as our community has done for a century and a half, in the service of the life of the university.”

Reading Dudley’s response, I felt first surprise then sadness. I’d hoped for Ted’s sake, the school would accept his suggestions and act immediately. Instead, by refusing his advice, the school served Ted DeLaney a final insult. When I called DeLaney to get his response, expecting his tone to be flecked with anger, instead what I received was a somber and tired voice: “I have cancer.”

*

The diagnosis was bleak: stage 4 pancreatic cancer–“The same kind that took down Steve Jobs,” said DeLaney. A cancerous lesion had corroded his liver and weekly chemo treatments rendered him listless and often confined to his home. Despite his exhaustion, life sped up for the tired professor in his final year teaching at W&L. His retirement compounded by his cancer, created an unprecedented urgency for those hoping to acknowledge his work at W&L. First came the invitation to give a speech on Convocation Day in the fall of 2018. Then there was the promotion from associate professor to professor. The committee voted unanimously in his favor. Next was a glowing profile in the student-run paper Ring Tum Phi, and finally the presentation of an honorary degree at graduation in May 2019.

“Enough of the accolades!” he wrote in one of the many emails he’d sent me over the year, alerting me of each new award or honor he’d received. I could tell from the way he wrote it and the fact that he sent it alongside a link to another award he received from the local chapter of the NAACP that he wouldn’t mind being honored a couple more times. Humble though he may have been, DeLaney also delighted in the flood of recognition. Partly because it genuinely surprised him. In his mind, he hadn’t done anything unique to warrant such praise. “I’ve never published anything significant,” DeLaney said of his legacy. But also because like many academics, DeLaney has an ego. What separates his from others though is his lack of presumption, his belief that nothing is owed, everything is earned. That’s why my lips curled upward and into a smile when he wrote to me to say, “Dear Abigail, I received a long-sustained standing ovation during the awarding of my honorary degree.”

As part of Ted’s celebratory send-off, a retirement party was thrown in his honor on the roof of the Robert E. Lee hotel in downtown Lexington a few weeks before graduation. I drove the seven hours from New York City to attend. I asked Ted if in-between all the festivities, he might have time for another chat. He warned me the weekend was fully booked but he’d try and find a moment for coffee. This time I knew better than to take him at his word. I arrived at his office once again at 8 am, my recorder fully charged, my thermos full of coffee, prepared to talk for at least three hours.

His office was a mess. Whereas before tidiness had prevented the space from seeming as small as it was, now stacks of papers and piles of books revealed just how little room there was for everything to fit. Things had been chaotic, he admitted. And in the midst of so much activity, perhaps he’d abandoned his typical cleaning routine. DeLaney himself looked neat as ever in a handsome blue blazer, pale yellow button down, and crisp pair of pressed khakis. The only thing different was his weight. He must’ve lost fifty pounds since the last time I’d seen him. DeLaney confessed to enjoying being able to fit into some of his older pants he’d long since retired from his wardrobe. He’d also enjoyed the recognition which he wasn’t convinced was unrelated to his diagnosis. “Perhaps I should get cancer more often,” he said, recounting joking to a colleague.

The irony of all the audulation was that it came on the heels of the school’s rejection of seventy five percent of the commission’s report.

“Were you angry when you read the president’s response?” I asked.

“I wasn’t angry, no.”

“Why not?”

I must’ve sounded incredulous or accusatory because he barked back at me “I never expected any of it to be accepted in the first place!”

Sitting in his office in the aftermath of his response, small noises came into focus. In the absence of our conversation I could hear doors opening and closing, loafers scuffling along linoleum floors, students and teachers chit-chatting in the hallway. I looked out the window and then over to Ted who was staring at his hands collapsed in his lap.

“One thing I’ve learned over a long life, is that to express anger doesn’t do anything for me,” DeLaney said quietly. “When you’re the stereotypical angry black man, doors close even more.”

Disappointment on the other hand can be profound. It’s the risk we assume when we choose to hope, and it was clear that DeLaney, despite claiming to know better, had let a little hope slip into his heart. He’d wanted to help the school that he loved improve in ways that were for him also deeply personal before he retired. It hadn’t turned out that way but for Ted DeLaney, it wasn’t the end of the world. He was disappointed he admitted, but what’s a little disappointment to a man who as he said with a shrug and a quiet laugh “has been disappointed all his life.”

Follow Abigail Covington on Twitter.